22/12/2016

Córdoba - Buenos Aires

I have finally made it to Buenos Aires.

4488 kilometres, five long bus journeys and four weeks after setting my foot in Lima, I am now on the Atlantic Coast.

My first task will be finding a place to stay for the month that I plan to spend here. Luckily an old friend, someone whom I haven't met for seven years, lives here. He's promised I can crash his couch for a few nights while looking for a room in a shared flat.

I'm eager to get to know the city. Right now all the different quarters are just names on the map for me. What kind of meanings will La Boca, San Telmo or Palermo carry in five week's time?

21/12/2016

Playa de los Hippies

The family

has promised to take me to the town of Jujuy, but to our dismay the car won't

start, and after trying for a while to get the engine going by pushing, I have to

give up and start a three-kilometre run to catch the bus that only runs once

every day.

After an

hour and a half of standing in an old rackety bus that anyone would have considered full

already before the last twenty people got in, I'm finally at the bus station in

Jujuy. It's almost 8 pm, and I find there is a night bus to Cordoba, 900 kilometres away, leaving in

an hour. I decide to take that instead of making my way straight to Buenos

Aires; I can still spend a day or two in Cordoba before reaching my final

destination.

Cordoba is

a university town, full of colonial and Jesuit history. I walk around the

streets and visit a museum on the "disappeared" people in Argentina

in the 1970s, but I'm mostly enthusiastic about the prospect of going to one of

the riverside beaches outside Cordoba.

On my second day, I catch a bus that takes me one and a half hours outside the town - but I'm late. It's already early evening when I get there, and I also don't have precise directions. I ask a girl in the bus, and luckily she and the three guys she's with are going to the same beach I'm looking for: La Playa de los Hippies.

On my second day, I catch a bus that takes me one and a half hours outside the town - but I'm late. It's already early evening when I get there, and I also don't have precise directions. I ask a girl in the bus, and luckily she and the three guys she's with are going to the same beach I'm looking for: La Playa de los Hippies.

Although it's embarrassing how hard it is for me to understand their Argentinian accent, I'm still happy to be with them, since it turns out the route is not that

straightforward. After getting out of the bus in the middle of nowhere, you

first have to walk, then call a kind of a taxi, and after the taxi trip either

pay for a canoe ride or walk over a hill for twenty minutes. As I haven't been

aware of all these extra expenses, I haven't brought enough money with me, and have

no chance but to hope I will find the right path over the hill. I say goodbye to the girl and

her friends, who sit down to wait for the canoe.

But the Playa itself is lovely. Indeed, it is a Hippie Beach, with tents and more permanent makeshift living constructions all around the shore, but it's all very peaceful. I'm almost the only person in the water. I float in the river and let the mild current carry me while the sun sets behind the hills.

When I begin my long walk back to where the bus left us, the moon has already risen to guide my path.

20/12/2016

16/12/2016

Reserva natural

I arrive at the farm by car in the early evening. It's not far from the town of Jujuy, but on that windy trail made of sand, mud and rocks, the trip lasts almost two hours. The car rocks and sways on the uneven road so that often I'm worried about it falling on one side. We cross many streams and little rivers by simply driving through them. Ever so often we stop to open a gate and then to close it behind us; they are for all the cattle and horses that roam free here.

The farm is small and surrounded by wooded hills. Not just surrounded: the farm itself is on a sloping hillside. There are two huts for the volunteers to sleep in; one that serves as a kitchen and a common space; and a house where the family lives themselves. There are no neighbours to be seen, no other houses anywhere on any of the hills as far as the eye can see.

I meet the other volunteers, a handful of young people from different corners of the world, who tell me of a river just down the hill. One of the farm dogs follows me to the river, and the cool water feels lovely after the warm day - but already halfway back up the steep hill, it's just as hot again.

The sun has already set behind the hills when I get back. Now it's time for dinner: we all gather around a long wooden table in the common room. After a delightful meal, the father of the family steps behind his DJ table, turns on the generator power and puts on some music. Saturday is their electricity day and therefore a party day. Outside the hills and the forests are dark and quiet, and in the middle of it is our cosy little hut, a festive atmosphere and happy voices shouting over the music.

But when I step outside, I am taken by surprise. It is not entirely dark. First I see one tiny light, then another, and then I realise they are all around: little sparkles in the bushes around me, above the grass, in the trees. They take turns in shining their light, and so the whole hillside glistens forming the most mesmerising backdrop. Thousands of them, millions of them. "Luciérnagas", the father tells me, "fireflies. This is their season." I stand spellbound, unwilling to go back in.

This is going to be my home for a week.

The farm is small and surrounded by wooded hills. Not just surrounded: the farm itself is on a sloping hillside. There are two huts for the volunteers to sleep in; one that serves as a kitchen and a common space; and a house where the family lives themselves. There are no neighbours to be seen, no other houses anywhere on any of the hills as far as the eye can see.

I meet the other volunteers, a handful of young people from different corners of the world, who tell me of a river just down the hill. One of the farm dogs follows me to the river, and the cool water feels lovely after the warm day - but already halfway back up the steep hill, it's just as hot again.

The sun has already set behind the hills when I get back. Now it's time for dinner: we all gather around a long wooden table in the common room. After a delightful meal, the father of the family steps behind his DJ table, turns on the generator power and puts on some music. Saturday is their electricity day and therefore a party day. Outside the hills and the forests are dark and quiet, and in the middle of it is our cosy little hut, a festive atmosphere and happy voices shouting over the music.

But when I step outside, I am taken by surprise. It is not entirely dark. First I see one tiny light, then another, and then I realise they are all around: little sparkles in the bushes around me, above the grass, in the trees. They take turns in shining their light, and so the whole hillside glistens forming the most mesmerising backdrop. Thousands of them, millions of them. "Luciérnagas", the father tells me, "fireflies. This is their season." I stand spellbound, unwilling to go back in.

This is going to be my home for a week.

15/12/2016

14/12/2016

Compras, parte II

The people

here like to cluster same kind of shops on the same street. I suppose it's

wonderfully handy if you're a local: when the first hardware store doesn't have

the kind of tool you're looking for, you just pop in at the next shop. When

someone tells you of a new cake shop, "on the confectionery street",

you'll have no problem finding it.

For a

visitor, however, it can be a nightmare. You're starving and wish to find one

single restaurant, but all the street has to offer is barber shops. You've left

your toothbrush in the last town and would simply like to clean your teeth for

the first time in three days, but there is nothing but wallpaper everywhere.

I've been lucky enough to also walk down a toilet bowl street and even a

dentist's chair street. Or this - costumes and party deco street. (Parties and dressing

up is important in these parts of the world.)

And what about my bikini?

Well, I finally stumbled upon my luck, when I had already decided I would not look one street further. I was knackered, disappointed and angry. I had asked at several clothes shops, underwear shops and sports shops, and walked past hundreds of other businesses.

Then one

saleswoman called me from a clothing store. It was one of those little shops

inside a kind of a small market hall that consisted of just eight shops on both

sides of a corridor. "What are you looking for, can I help?" she

asked, and resigned, I answered, "You surely don't have bikinis, do

you?"

"Of

course we do!" she answered briskly. She was there with a friend, both of

them in their fifties. The shop was perhaps six square metres and covered from

the floor to the ceiling with clothes that looked like they were all about to

fall from the shelves. Eagerly, the woman pulled a plastic bag from one of the

shelves, and together with the friend, they started emptying its contents onto

the counter.

There was a

swimming suit and two sets of bikinis. No different colours, different models,

not even different sizes. Just those three, take it or leave it. The women

lifted the bikini tops to hold them over my chest; that was the amount of

trying on there was to do. They concluded that the black one fit me perfectly.

I left the

shop with a new black bikini in my bag.

In general,

I try as much as possible to avoid posting photos of people without their

permission, unless they are in large groups and thus not that intimately

portrayed. In this post, however, I felt like it would have been impossible to

picture the topic without showing a couple of faces too.

13/12/2016

Compras, parte I

When

travelling, one encounters a stunning number of surprising things. The people

look different from those at home. They speak a strange language. The climate may

be completely different and the weather might do unexpected things. The houses

look probably different, the food tastes unlike anything you've tasted, and

such everyday things as doing sports, using the bathroom or taking a bus may

leave you at a loss.

But there's

one thing that surely must be more or less the same everywhere: shopping! All

over the world, people need groceries, toothpaste and underwear, right? Walk in

the shop, make your pick, pay, done?

Haha. Ha.

Case Study

Bikini:

I had

arrived in Lima just a few days earlier, and I knew I was going to visit some

hot springs near Machu Picchu in a couple of days. As my next destination,

Cusco, was up on the mountains and nowhere near lakes or the sea, I figured I

should try to find a swimming suit already in Lima, just to be sure.

Just to be

sure! After having wondered around the streets for three hours, I gave up on

the other thing on my To Buy List, a sleeping bag; I was exhausted and decided

that in addition to sleeping without a mattress the next couple of nights, I

would also have to sleep without any covers. But the bikini was more important.

I was not going to miss out on the hot springs after hiking up and down

mountain paths for two days.

Typically, I assume, people in Peru and Bolivia buy everything they need from

tiny stores which are just a couple of shelves or even just one stand. The most

common form of it is a street vendor's stand, and it can sell anything. That

is, anything within a range. The

problem is that what belongs to a range might not be that

obvious for a foreigner.

There's the

cosmetics stand, with hundreds if not thousands of little products arranged

meticulously under one big umbrella - but if you're looking for toothpaste,

you'll be met with just an apologetic (or disgusted) shake of a head. There's

the underwear stand with its selection of simple white cotton knickers, plush

red lacy underwear and the daring lean G string - but of course no swimwear.

The bakery stand has all kinds of tempting-looking sweet goods but definitely

no bread. And so on.

Even when

things are not sold on the streets, the indoor stores are hardly any bigger.

They come mostly in a cluster of little shops, much like a market hall, but so

tiny that the salesperson barely has room for that one chair that he or she

sits on. They can sell fruit, or hardware, or mobile phone parts, anything.

Just that the range is always very restricted. Services are possible too: I've

seen several shoe repair shops that have made me take another look in

astonishment, as it seems that no one can repair anything is such a confined

space.

In Lima,

and even more in La Paz, I also saw some more Western-style shops, with enough

room for the customers to walk in and look at things. Presumably they are there

just for the tourists and the richest of the rich, though. And even though I

browsed through those, too, on my bikini-searching quest, I didn't find one - or then they had a

selection of just two models in horrid eighties' Hawaii-style colours and

patterns.

(to be continued!)

(to be continued!)

12/12/2016

Memorias

At times, this journey has made me think of the seven months that I spent in Central America some years ago. My old blog still exists; I can hardly believe it's been nine years since I wrote about our life in Nicaragua, the hikes to the lagoon, the Granada Poetry Festival, and our trip to Miraflor.

When I wrote my final entry, remembering in a collection of photos everything I had seen in those seven months, I was already pregnant. Why, my son will turn eight in a few weeks.

When I wrote my final entry, remembering in a collection of photos everything I had seen in those seven months, I was already pregnant. Why, my son will turn eight in a few weeks.

11/12/2016

10/12/2016

Dos mundos

"That's

something you'll see everywhere in Latin America", said my first

Couchsurfing host in Cusco. "An upper-class neighbourhood can turn into

a slum just from one street to another."

Often,

however, the change is even more drastic: you see it from one house to another.

Coming from

such a different culture with such different problems, it's difficult to

understand the issues here. I can't tell if people are starving or how severe

of a problem child labour is. I can't say whether poverty always means a dangerous

neighbourhood, or whether a dangerous neighbourhood always means poverty. There

are teenage street vendor girls with their sulky teenage faces glued to their

smartphone screens, and middle-aged street vendor mothers with their three

little children playing in the dirt next to their stands.

What I

noticed already in Lima, however, is that it's as if there were two completely

different economies existing side by side within the same city or the same

country. That's possibly the case in Europe, too, but the differences are not

quite that extreme.

Here, there's the first economy, where a person can buy a bagful of groceries from a supermarket for about 12 euros, take a city bus for some 40 cents and a taxi for perhaps 4 euros, go to a yoga class for 6 euros and buy a fresh fruit smoothie for 2 euros.

And then

there's the other economy. For those people, taking a bus would be too

expensive, so they walk. They buy their groceries from a market where they can

choose the cheapest vegetables and haggle the prices down. They might have a

fresh fruit smoothie when it's mango season and they walk past a tree that

belongs to no-one. For those people, the other economy doesn't exist. The cable cars might float above their homes night and day, but they belong to another world beyond their reach.

Still,

those people are not unemployed, or alcoholic, or homeless. They have jobs and

they work long hours, and their children presumably go to school just like

everybody else's. A bit of public education just isn't enough. The system we

have in place works the same way here as it does everywhere: those who have

some wealth tend to have it easier to gain more.Those who have none have it much harder ever to gain any.

09/12/2016

Why I don't visit churches

I don't do

cathedrals.

For sure, they can be full of fantastic art and give us meaningful insight into the beliefs and ways of life of the past. That's all great. I might peek in one if I happen to stumble upon one and feel like some solemnity might be in order. But seriously, when you enter your fifth cathedral, do you still remember the first? When you've read the plate about the painter of the frescos, taken a picture of the altar and stepped back out into the sunshine, has any of it stuck with you?

For sure, they can be full of fantastic art and give us meaningful insight into the beliefs and ways of life of the past. That's all great. I might peek in one if I happen to stumble upon one and feel like some solemnity might be in order. But seriously, when you enter your fifth cathedral, do you still remember the first? When you've read the plate about the painter of the frescos, taken a picture of the altar and stepped back out into the sunshine, has any of it stuck with you?

I'm wary of

museums, too. If I live in a place for a year, then, of course: I'll probably

visit most of them. I'm profoundly interested in history, politics, art, design – all that stuff that museums are usually good at. But a museum run in the sense of

a pub crawl is beyond the point. On this trip, as I've been constantly moving from place to place, I still haven't been inside one

single museum.

You know, there are

these guide books, "Lonely Planet" they are called, and they are awfully

popular. You'll find them in the backpacks of almost every traveller in almost

any hostel. At the tables of the hostel bar, the backpackers compare notes with

each other and discuss which Lonely Planet recommended experience they have or

haven't done yet.

One series of books the Lonely Planet Corporation has is called X on a Shoestring. It's for people for whom seeing a country or two

isn't enough; they want to travel at least half a continent. Europe on a Shoestring. Southeast Asia on a

Shoestring. The World on a Shoestring (coming up). The word shoestring is supposed to refer to cheap

travel, but in my mind, it evokes an image of someone drawing a line from the

main attraction to another onto a map with the help of a string and then

sticking to it.

I used to

own one of those books too, years back, and I know what great writers they

have. All you have to do is to open one of them, any of them, and you'll feel like you're

missing out on some great fun somewhere in the world. "Be sure not to miss

the amazing experience of...", they'll write. "Ideally, you'll get to

X the night before, do Y and Z, and then get up early the next morning

to..."

And the

readers do! They dash from rafting to horseback riding, from canopy tour to hot

springs, from mountain biking to temple ruins, from bird-watching to swimming

with the dolphins. And inside cities, from cathedrals to museums. Tick-tick-tick,

they tick off to-do lists in their guidebooks, click-click-click, they snap the selfies with the temple ruin or

the friendly dolphin, tap-tap-tap they

post them for the world to see. At the end, they'll feel like they've seen

everything there was in the country to see.

What I like

to do is watch. I watch people, how they go about their life, what kind of work

they do, where they go. I listen to the people on the streets and buses, see

how they talk to their friends, partners, or strangers. I observe how mothers

and fathers behave with their children, what children are allowed to do and what

not, how the children play and how they talk to their parents. I look at what

people eat and what they buy, what happens in situations of buying and selling,

what kind of shops there are.

I look at

how people have decorated their houses or their yards. I watch celebrations of

birthdays or other parties in the streets or in parks. I try to find places

where I can hear people sing or see them dance. I go to places where local people go: bus stations, cinemas, educational institutions, vegetable markets. I visit parks and squares and observe how people spend their free time, and what kind of people seem to have free time. I look at how people laugh.

Whenever I get the chance, I talk with the locals and ask them questions, but I rarely approach complete strangers – as an intruding outsider, I feel I don't have the right. I like to remind myself that whenever I set my foot in some city, I'm stepping into other people's home, and none of that was made just so that I could have a great experience.

Before I arrive, or during the first days, I try

to read or hear and understand as much of the local history as possible. After

that, I just breathe in the way of life. There's so much of it, you don't have

to worry about it running out anytime soon.Whenever I get the chance, I talk with the locals and ask them questions, but I rarely approach complete strangers – as an intruding outsider, I feel I don't have the right. I like to remind myself that whenever I set my foot in some city, I'm stepping into other people's home, and none of that was made just so that I could have a great experience.

Labels:

cathedral,

city,

couchsurfing,

historical,

lapaz,

lonelyplanet,

metropolis,

museum,

tradition,

travel

Cine

In La Paz, it's even harder to find anything vegetarian to eat on the street than in Peru. On the second day, after walking for hours and eating only biscuits, I give up and look up a veggie restaurant in town. This will save me from starvation.

On my way to the hostel, I stumble across a demonstration on the Plaza Mayor. A big demonstration. The people have filled the whole square, amongst them children, young and old people. It's not a very warm day, and everybody is wearing jumpers and jackets. Some have taken over the balcony of a building. Street vendors mingle among the crowd as usual.

Afraid of appearing blatantly ignorant of some hugely topical issue in the country (or being punched by some frenzied demonstrator), I choose not to ask anyone what the protest is all about. I try to read some of the banners, but they don't reveal the mystery either ("30 mega projects -> 30 disasters!"). Instead, I ask the kitchen worker of the hostel when I get back.

"Oh, it's about water", she says. "Water?" I enquire. She tells that there is a serious water shortage in the city and people are at the end of their rope. "And the government doesn't do anything", I suggest to empathise with the protestors, but she says it isn't really the government's fault. "You know, the water is gone", she smiles helplessly. "Climate change."

I spend the rest of the day roaming the streets of unknown neighbourhoods and find the cinema on time by 7:30. It turns out that the old beautiful building is actually a municipal theatre and the film to be shown is a work of some film students. Both the elf and the punk show up to accompany me, and once we have taken our seats, I ask the girl why she has left Chile. "Chile is terrible!" she exclaims. I'm surprised. What's so bad about Chile? "The people", she replies. "They're awful. I like Columbia, Bolivia and Paraguay."

Then there are four young men on the stage in suits, and the one holding the microphone is almost in tears, talking about the overwhelmingness of finally seeing their film being screened. But when the film – a drug mafia crime thriller – begins, it is so badly made (even for a student film) that we decide to leave half an hour into the start. I'm not disappointed, though. It's been a good La Paz day.

Labels:

altitude,

bolivia,

capital,

centre,

city,

climate,

climate change,

elevation,

film,

food,

lapaz,

metropolis,

movie,

vegetarian

08/12/2016

Loco

I came to

the city with no expectations, literally just because it happened to be on the

way. And it blew me away – just with its insanity. La Paz is a crazy city.

First, for about the last hour or two before arriving, there is no road to speak of. There is just dirt and dust, and sometimes the bus I was in had to cross small rivers or flooded ditches, seemingly by driving right into them and hoping for the best. Swaying and sliding amongst the mud and stones, and began to realise why the bus was kind of small.

On the sides of the dirt paths were buildings that were all made of the same red tile and seemed to share something else too: it looked like nobody was living in them. In fact, the majority didn't even have a roof. Still they stood there, hundreds of them, for miles and miles. Sometimes we saw a few people walking on the street, signs of life amongst the calm ominosity. On the walls of some houses, adverts had been scribbled with big letters on white chalk, such as "ELECTRICIAN" followed by a telephone number.

After reaching the outskirts of the city, there is still a good half an hour's descend to the city itself. La Paz has been constructed in a canyon surrounded by several mountains. The highest of them is the snow-covered Illimani, which can be seen from most parts of the city.

As I had arrived without knowing anything of the place, I resorted to the Internet. I learned that the city was founded in the 16th century and is not particularly big with under one million inhabitants. With altitudes varying from 3200 to 4100 metres, La Paz is the highest capital in the world. This means that there is very little chance for a fire; the oxygen in the air is so scarce that the flame burns only feebly.

With a variety of elevations, an underground train would not perhaps make much sense. That's why the Paceños commute by...dashing through the air?! The public transport system of gondola lifts, Mi Teleférico, was opened only two years ago and is strikingly modern. There are three lines in operation at the moment, and at least four more have been planned.

It's no wonder one would look to the skies for a solution to the transport problem. When I take my Virgin La Paz Walk, I see that the old, narrow streets are so packed with cars and minibuses that none of them seems to be moving anywhere. There isn't much room for people either, with the sidewalks full of street vendors sitting next to their banana pile or standing in front of their food cart. The feeling of crammedness is overwhelming.

Still, I can't help liking the city. The buildings are of varying ages, filthy but beautiful. The feel of La Paz is perplexing. Contrary to what the ghost town and the dirt road just before the city made me expect, and despite the street vendors and chaotic streets, the people seem– – –well, more familiar to me. (I refuse to say 'European' or 'Western', although I acknowledge the facts: having grown up in the so-called Western world, that is what I feel familiar with.) It's hard to put one's finger on it, but when I look at people, it's easier for me to understand what they do.

There is a different kind of diversity compared to the other places I've seen on this journey. The first thing I notice is a music conservatory. There is a large, beautiful bus station building. There are Italian restaurants. Daycares. Girls with a side cut or a nose piercing, next to the old women in their traditional costumes and the q'ipirina on their back. A group of teenagers going to the cinema, a couple of students coming from the university. Even people who, despite belonging to a gender or sexual minority, appear not to be living in the closet.

And although there are seemingly no tourists in the areas I walk in, I realise people don't stare at me. I no longer stand out like a sore thumb, and it is a huge relief.

First, for about the last hour or two before arriving, there is no road to speak of. There is just dirt and dust, and sometimes the bus I was in had to cross small rivers or flooded ditches, seemingly by driving right into them and hoping for the best. Swaying and sliding amongst the mud and stones, and began to realise why the bus was kind of small.

On the sides of the dirt paths were buildings that were all made of the same red tile and seemed to share something else too: it looked like nobody was living in them. In fact, the majority didn't even have a roof. Still they stood there, hundreds of them, for miles and miles. Sometimes we saw a few people walking on the street, signs of life amongst the calm ominosity. On the walls of some houses, adverts had been scribbled with big letters on white chalk, such as "ELECTRICIAN" followed by a telephone number.

After reaching the outskirts of the city, there is still a good half an hour's descend to the city itself. La Paz has been constructed in a canyon surrounded by several mountains. The highest of them is the snow-covered Illimani, which can be seen from most parts of the city.

As I had arrived without knowing anything of the place, I resorted to the Internet. I learned that the city was founded in the 16th century and is not particularly big with under one million inhabitants. With altitudes varying from 3200 to 4100 metres, La Paz is the highest capital in the world. This means that there is very little chance for a fire; the oxygen in the air is so scarce that the flame burns only feebly.

With a variety of elevations, an underground train would not perhaps make much sense. That's why the Paceños commute by...dashing through the air?! The public transport system of gondola lifts, Mi Teleférico, was opened only two years ago and is strikingly modern. There are three lines in operation at the moment, and at least four more have been planned.

It's no wonder one would look to the skies for a solution to the transport problem. When I take my Virgin La Paz Walk, I see that the old, narrow streets are so packed with cars and minibuses that none of them seems to be moving anywhere. There isn't much room for people either, with the sidewalks full of street vendors sitting next to their banana pile or standing in front of their food cart. The feeling of crammedness is overwhelming.

Still, I can't help liking the city. The buildings are of varying ages, filthy but beautiful. The feel of La Paz is perplexing. Contrary to what the ghost town and the dirt road just before the city made me expect, and despite the street vendors and chaotic streets, the people seem– – –well, more familiar to me. (I refuse to say 'European' or 'Western', although I acknowledge the facts: having grown up in the so-called Western world, that is what I feel familiar with.) It's hard to put one's finger on it, but when I look at people, it's easier for me to understand what they do.

There is a different kind of diversity compared to the other places I've seen on this journey. The first thing I notice is a music conservatory. There is a large, beautiful bus station building. There are Italian restaurants. Daycares. Girls with a side cut or a nose piercing, next to the old women in their traditional costumes and the q'ipirina on their back. A group of teenagers going to the cinema, a couple of students coming from the university. Even people who, despite belonging to a gender or sexual minority, appear not to be living in the closet.

And although there are seemingly no tourists in the areas I walk in, I realise people don't stare at me. I no longer stand out like a sore thumb, and it is a huge relief.

x

07/12/2016

Lago Titicaca y el camino a La Paz

My second long bus journey: 17 hours.

Puno, Peru

At a little past five in the morning I wake up as the bus arrives in the town of Puno. We're told we'll have to continue with another bus in about two hours. I succumb to the circumstances and get myself a map of sorts copied on a piece of paper. Then I realise that Lake Titicaca is just behind the bus station.

Titicaca is a lake situated at some 3,800 metres above sea level and is almost the size of Uusimaa (and could fit nine Berlins in it). As such, it is considered to be the highest navigable lake in the world.

It's beautiful. And dirty.

The air is still cool this early in the morning when I stroll along the shore of the lake. There are people on their morning jog. And dogs, always dogs.

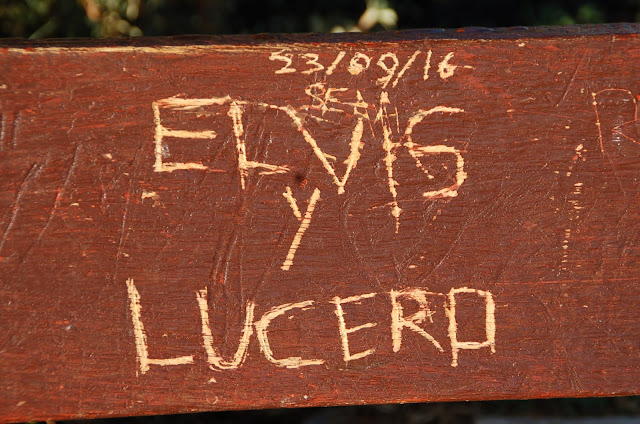

Elvis and Lucero, of the Titicaca Shore Bench, would like to send their greetings.

The contrasts are striking, as always.

I buy my breakfast - two rolls with avocado and salt - from the lady with a bike vending stand and get on the second bus.

After just a couple of hours down the road with the lake most of the time visible on our left, we arrive at the border. After a brief stop to have our passports stamped, we cross over to Bolivia. (The large white building is the Border Control office. The smaller one is a public bathroom.)

Cobacabana, Bolivia

In Cobacabana, we're once again told there will be a two-hour wait before the next bus. It's a happy surprise; now I'll have time to walk around Cobacabana too.

Now, if you come on a horse from the nearby village to visit a friend in town, a part of you might find it smart to tie the horse somewhere while you're gone...but then again, why bother. (I watched the horse for a good half an hour, and while nobody came to look at it in that time, it didn't seem to bother or be bothered by anyone either.)

San Pedro de Tiquina, Bolivia

One more surprise for the day: we have to cross the lake. (Later, looking at the map I realise that the border runs in such a peculiar manner that crossing the lake is the only way to not end up in Peru again.) There are boats that have been especially constructed to carry buses. They are long and low and wooden, and quite unlike all the other ferry boats I've seen before.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)